On Thursday, December 6, 1917, an American ship loaded with explosives bound for the European war detonated in the harbor at Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Almost 2000 people were killed and 9000 were wounded, straining the medical facilities of the area.

Soldiers recuperating from World War I injuries became the new, immediately deputized hospital orderlies, as every even semi-ablebodied person was pressed into service. If a given person was walking, seeing and hearing, he / she was qualified. Not too much attention given to examining credentials.

The YMCA was converted into a makeshift hospital within hours. When a local medical school was appealed to for volunteers, some were sent there, including fourth-year medical student Florence J. Murray, a minister’s daughter from rural Nova Scotia. Since the blast broke windows at their university’s campus two miles away, the medical students knew their time to help had come.

When Murray reported for duty at the YMCA, the commanding officer asked her, “Has your class had instruction in anesthesia?” “Yes, sir,” Murray replied, although years later she admitted, “The was no opportunity to say that everyone in the class except myself had had this training. In the army one doesn’t explain.”

Murray’s answers were good enough for the C.O. “Go to the operating room and give anesthetics,” he ordered, and she did as instruced. Her first patient was a six-year-old girl who made her pause. “Did a child require as much anesthetic as an adult, or should she have a smaller dose?” she wondered. “I did not know. I knew I should watch the eye reflexes to help judge the depth of the anesthesia, but unfortunately the child had lost both eyes.”

Too much anesthesia and the child could die; not enough and the child would experience horrendous pain. How stressful to not know what to do.

Murray simply had to wing it. “In fear and trembling,” she recalled, she gave the child a smaller dosage, then watched very closely for a reaction of any sort during the operation. Miss Murray had guessed right, and the patient came through the surgery nicely. Murray moved to the next surgery.

“The next morning,” she said, “the commanding officer appointed me official anesthetist of the hospital.”

Many have found themselves in stressful circumstances that stretched them and called forth from them their best.

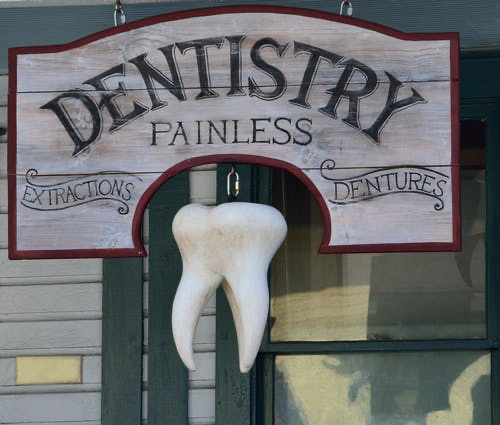

For example, Al McElheran, an Action International Ministries missionary, knew nothing about pulling teeth. But since he had made many trips into the interior of Ecuador and was trusted by the natives, they came to him with tooth aches. The logic was simple – “Brother Al, you are educated and you can read. You have brought us spiritual truth, and we know you. We trust you. We need you to stop this pain – please pull this tooth.”

So Al has pulled a lot of teeth over the years, having gone to Jungle Dentistry School.

Who knows when we will be called upon to say with Esther, God has placed me here in this critical moment to stand up and speak up and serve. I am here “. . . for such as time as this” (Esther 4:14).

Source: The Great Halifax Explosion, by John U. Bacon, pages 370 – 374.

Recent Comments