Part 3 reported on Mr. Stewart’s difficulty getting out of Hollywood and into a combat flying roll, coming to England and his promotions, his leader-ship, and Operation Argument in February, 1944.

On March 22, 1944 approaching aircraft manufacturing facilities at Oranienburg and Basdorf, Germany, Stewart’s bombardier shouted, “This is pea soup. We can’t do anything through this.” So what should Major Stewart do? Yes the plane was radar equipped, yes the Mickey should work in such conditions, but how do you hit a specific block from 21,000 feet through a layer of clouds? Do you waste the bombs? Do you kill a bunch of civilians?

With two hundred B-24s flying behind him, our man considered his options. His secondary target was Berlin. The Big B was where Germany air defenses were the best she had. He knew he might never get back. He also knew there were 200 crews of ten men each behind him. Looking below into the soup made his decision for him. “Switch to secondary target.” Thinking inside those 200 planes changed in that instant. Berlin was a general target (the goal being to demoralize the German population), not a specific one, so he could bomb the area, not a specific target.

Amazingly they did not lose any planes, but strain continued to mount in our hero. He kept his thoughts to himself, but his gray complexion, inability to eat, and shakes said it for him.

Major Stewart—seen on the right at left going over maps of the target—did not bring everyone home, but his numbers were extraordinarily good in a combat environment where losses were high and morale sometimes wobbled. His “luck” was based on precise flying and on smart decisions large and small, decisions that mid-30-year-olds made more often than a younger, less experienced lead pilot. And it did not hurt that the major had been a success in motion pictures, where he had dealt with the major generals of Hollywood—Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg. His men loved him and everyone looked up to him.

He had taken on enormous responsibility—the kind normally reserved for career military West Pointers. But he knew that occasionally his mind was scrambled and that put men under him in danger.

The military brass were re-thinking Hollywood airmen. Jimmy Stewart’s sidekick, Clark Gable, had flown four missions as a B-17 waist gunner. But leadership became convinced he had a death wish after the passing of his wife, Carole Lombard, and freed him to return to Hollywood.

Washington fretted about what a prize he would make if shot down over Germany. What would Hitler do with an American movie star in captivity—the one who had made The Mortal Storm back in 1940, which exposed the evils of Nazism to millions of moviegoers? Parade him through the streets of Berlin? Parole him in exchange for Hess?

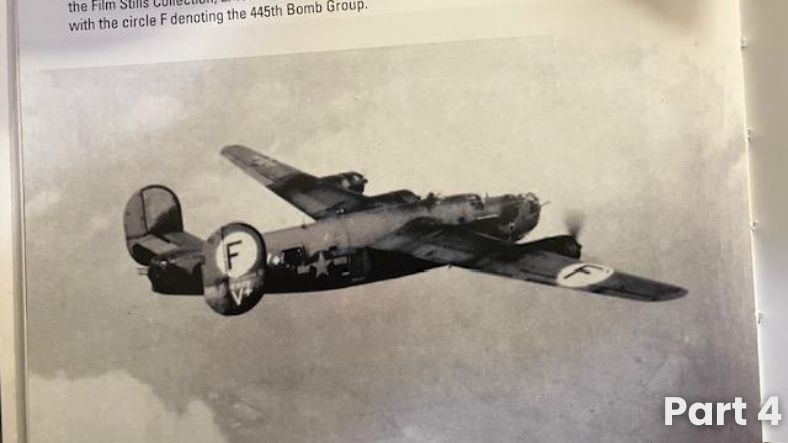

To the great heartbreak of the 445th Bomb Group, Major Stewart reluctantly accepted flying a desk (except when desperately needed to command a mission). But by April 10, Major Stewart was back in the air on a mission over Germany, but not as pilot and not with his beloved 445th. He would later reflect, “. . . all my efforts, all my prayers couldn’t stand between them and their fates, and I grieved over them.”

When he was not flying, Stewart’s 15-hour days had a steady, positive impact serving from the ground. Invasionitis (the happy disease of anticipating the June 6, 1944, invasion of France under Eisenhower) had a lifting effect.

Jim continued to fly. For example, on July 19, 1944, some twelve hundred B-17s and B-24s pounded ten military targets in western and southwestern Germany. Another flight was on November 30, 1944.

Then winter closed its fist on the air war. Even so, the Eighth swung into action to defeat the dreaded Panzer divisions’ advance into the Ardennes Forest of Belgium (what’s known as the Battle of the Bulge). German tanks were abandoned simply because they literally ran out of gas.

But Hitler still had one amazing development—the jet fighter Me 262. Compared to that plane, the B-17 seemed to be standing still. So no one took a mission over Germany as a gimme, not even as the ground forces of Soviet General Georgy Zhukov closed in on Berlin.

On March 21, 1945, one year after he flew over Big B, full Colonel James Stewart climbed into the bomb bay of a B-24 one last time as Second Wing commander in one of 1400 Eighth Air Force ships attacking ten airfields inside Germany. Under camouflaged shelters next to runways sat a full complement of Me 262 jet fighters that had been dealing death to the Eighth.

Even with minimal flak and no German fighters opposing them, some confusion in the air—missed targets and having to avoid another group of American planes—even though all the planes returned safely—Stewart’s shakes increased. It was one mission too many. It was a failure of a mission in his eyes, even though they had smashed the target and he received public commendation. He was now an earth-bound former Hollywood star, a man wrung out by the rigors and horrors of war facing an unknown future. His sixteen months of combat were over.

Returning home, Stewart was mum on his war experience. People who stayed stateside could not understand what he had gone through. He refused to talk about his war experiences. What does one say about seeing a B-24 shot to pieces beside him and fall out of formation in a fireball? All the letters he wrote home to parents whose sons had died? Why would he want to talk about his rare failures as a leader? Why share about a dozen planes dropping bombs on an innocent French town?

In no hurry to get married, he waited three more years after returning home to marry Gloria Hatrick McLean August 9, 1949. After 44 years of marriage, Gloria died in 1994 so Jim lost his fighting spirit.

As the war ended, Mr. Stewart was about 37 years old, the grand old man of the 445 and the 453. Friends were shocked by his appearance; bags under his eyes and furrowed brow. His full head of hair had begun to recede and was half gray. He had grown even thinner.

Mr. James Maitland Stewart was the commander of the Second Combat Wing of the Eighth Air Force, a valued officer, a recipient of the silver eagles of a full colonel. He flew twenty combat missions over Germany. He received the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Croix de Guerre (from France).

He did not command a combat flight after March 21, 1945. But there was little left to bomb. Hitler committed suicide the last day of April. The war in Europe ended May 7, 1945.

In 1976 Jim returned to England. At left he leans on the Operations building at his old base in Tibenham.

Mr. Stewart returned home and continued in movies and television, but with age, came declining energy and fewer roles. He died in 1997 at age 89.

Mr. Stewart never lost the humility and reliability that made him a star in the first place. While I do not admire his personal life, nor his non-response to the Gospel (as far as I can tell), Mr. Stewart is to be commended as a fine patriot who rendered valuable service to America during World War II.

Keith Kaynor

Recent Comments