Part 2 reported Stewart’s time at Princeton University, his interest in flying and the theater, his relationships with women, and moving toward military service.

Seeking a commercial pilot license, Stewart had to:

- Execute a succession of figure eights around two pylons a certain distance apart which is not easy in a limited amount of specified space

- Come in from 1000 feet up and stop your plane on the ground within 40 feet of a certain white line

- Go into and get out of tailspins

- Fly by instruments

- Pass a four-hour exam.

The Battle to Get into the Battle When a draft board letter finally came, it informed him he was underweight. He stormed inside and wanted to talk with Louis B. Mayer (of MGM fame). “Did you talk with the draft board? Did they reject me because you interfered to protect your investment?” He needed a solid answer before facing his father who would not be happy with any deferment. When Dad found out, indeed there was an unpleasant conversation.

Desperate to put on weight to reverse his 1 – B selective service status, Jimmy sought out the local draft board doctor. By March, another letter came, this time with the coveted order to report for duty. He would follow in the footsteps of other Stewart men. He would do what his ancestors had done: feed a restless spirit on a huge stage for drama.

Precisely because he came to the airport every day fully prepared and had not only gone by the book, but absorbed it, he earned the coveted rating of a commercial pilot. Coupled with a degree from Princeton, he assumed he would be welcome in the Army Air Corp in spite of being 33 and still rail thin.

Movie executive Louis B. Mayer wanted Jim to fulfill his military obligation by working with the Army Corp Motion Picture Unit. Mayer argued that Jim could do a great deal more good for the war effort as a recruiter than he could as one man in an airplane. And he had been in touch with Washington to prevent that from happening

Mr. Stewart was livid with anger. Though Jim turned his back on Hollywood—he was bored and ready to do something different—he was mobbed at a farewell dinner. The press hounded him during training.

England and promotion Eventually Mr. Stewart was shipped to England. So exemplary was his service that he was named a commanding officer of the 445th Bomber Group after a mere 2.5 years of serving in the Air Force.

Stewart became a veteran pilot in a few short months. The stress of combat, with lives on the line, had a sudden and maturing impact. He rose to the challenge. Nothing like risking your life to motivate and refine one’s skills. While maintaining the distance between officers and enlisted men on his planes, Steward found ways to connect and bond with his men. Once after a tough day over Germany, he took up one young man for some softball flying—like buzzing the tower, waking the commander from his nap. When the purpose was explained to the commander, the incident never got into his personnel file.

Ground Crews During the air campaigns of 1943 and 1944, Stewart grew more aloof than ever, more buried in his work of keeping the squadron flying and his men in good spirits. The ground crews worked as hard as the fliers to keep the B-17s and B-24s in the air, so he visited them often and kept conversations going.

Cold On missions Nine Yanks and a Jerk, Georgia Peach, Sky Wolf and other airplanes fought high winds, heavy overcast, and malfunctions of the bomb racks (one rack out of four failed to release) due to alternating high humidity and deep, subzero freezing. Out of a flight of 22 planes, seven dropped out because of a critical system being frozen. Machine guns froze, oxygen masks froze—men had to break ice off them to continue using them—everything froze except the hot-burning engines. Some attitudes brought on massive malfunction—40 below zero will do that.

Substituting Fighter Pilots When B-17 pilot Emmett Watson crashed, he was incapacitated so Mr. Stewart had to press a fighter pilot into the left seat to fill out the crew of Dixie Bell. This was a problem! Fighter pilots did not want to fly a B. The B-17s and B-24s were slow and presented a huge target to enemy fighters. Feeling responsible for such personnel switches, Stewart worried about the adaptability of such thrown-together crews. Lots of second guessing and “what ifs.”

Stress Little time to think. Too much time to think. Missions started with a wake-up call at 3:00 A.M. Major Stewart was already awake, having slept little. How can I command when my mind is filled with fear. He remembered what his father had told him, “Every man is afraid son, but remember you can’t handle fear all by yourself. Give it to God. He’ll carry it for you.” Jim apparently carried the book of Psalms with him in his flight suit, along with his lucky handkerchief.

Leader By Stewart’s ninth mission (25 missions earned a pilot a ride home, but few made 25), his commanding superiors had confidence in Stewart’s leadership. He led. Made the tough calls. Was the man.

War is Hell On October 14, 1943, sixty planes were shot down. On another day 72 were shot down. On a third, 13 planes out of 25. Stewart assumed it was only a matter of time until he was shot down. He had the shakes. He could not keep anything down and survived the war on ice cream and peanut butter. His health was fragile.

On one flight there were 125 airplanes, that’s 500 throbbing engines—a thundering armada, bristling with explosives.

On Friday of Operation Argument week, in February, 1944, a staggering 754 airplanes—B-17 and B-24s, escorted by twenty groups of Eighth Air Force fighters and twelve squadrons of Royal Air Force Spitfires and Mustangs—assaulted southern Germany’s three Messerschmitt aircraft production centers and a ball-bearing plant. The briefing prior to flight time stressed the need to conserve fuel because the planes carried ten hours’ worth and would be flying at least nine and a half hours. Jim Stewart sat in the copilot’s seat, but as group commander in ship 447, Dixie Flier.

Lots of anti-aircraft flak and fighters, the planes limped back to the British air base. Severely damaged planes (mostly hydraulics necessary to steer an airplane) or planes with wounded aboard, could request immediate landing by lighting a flare. If we can only get down safely, a shot of whisky, a meal and a bed await. Dixie Flier waited her turn; then with final convulsions, and physics beyond the capacity of any structure, rolled to a stop. Old men in their 20s poured from the plane exhausted.

This was Major Stewart’s tenth mission, earning him an Oak Leaf Cluster. The author claims that meant nothing to him; getting his boys back home meant everything. But after ten missions, he was ready to unravel.

When an American bomber was hit and men were able to bail out, the German fighter pilots backed off until the fliers were comfortably below them—a gentlemanly thing to do. Describing another flight, author Robert Matzen wrote, “Wright Lee of 1st crew of the 702nd Squadron said fighters were pouring their bullets into the nose of the plane, hitting bombardier Cassini a dozen times and ripped the thumb off Lieutenant Massey. The blinding flash of an exploding 20mm shell injured others. In desperation the surviving pilot lowered his wheels, an act of surrender. The Luftwaffe recognize the signal and as a professional courtesy, backed off, allowing the surviving crew members to bail out before attacking again.”

Wright later admitted he was tempted to chuck it all . . . bail out since survival on the ground (even in the hands of the Germans) had a higher survival rate.

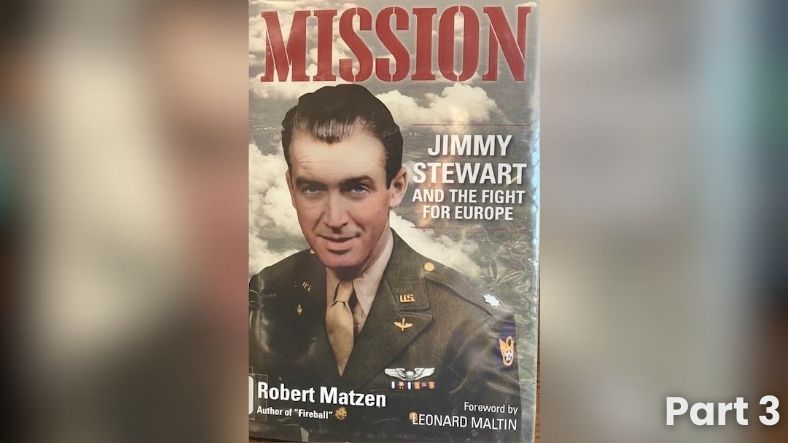

Stewart, shown in this photo, was dressed for flight—long johns, heated blue bunny suit, shirt, tie, pants, coveralls, jacket, scarf, and gloves, all needed to hold off forty- degree-below-zero cold

Operation Argument had been costly. This week of intense bombardment in February, 1944—Big Week—was costly to Americans. Costly also to the Germans who lost 456 fighter planes trying to beat back the American bombardment. For every American aircraft downed, the Germans lost ten. The manufacture of German fighter aircraft continued at a record pace, but who would fly them? They were running out of pilots.

. On March 8th, Major Stewart was flying in an air armada of 300 Flying Fortresses and 150 Liberators against a ball-bearing plant in Erkner, just southeast of Berlin. The next day, the B-17s struck Big B—Berlin itself.

Major Stewart had been shaken by the March 8th mission, and did not fly for two weeks. Returning to the cockpit, Stewart was short-tempered. His nerves were shot; he was in no mood to be patient.

On another bombing run, some sensitive equipment became unstable just as cloud cover obscured the target. Major Stewart had to make an instantaneous decision—bomb blind through the clouds or climb, go around, and come in again hoping the equipment would work on a second try or the cloud cover would clear, but exposing themselves to more accurate anti-aircraft fire and renewed German fighter planes.

Jim sweated, then held up the bombs. The formation circled around and came in for a second attempt. Enemy fire intensified, but all planes returned to England safely. Major Stewart showed mature piloting skills, and mature command decisions, even as he knew he was hanging on by his fingernails.

The generals knew Stewart had made the 445th a tightly run, successful outfit. But they did not know and could not predict how long he would be able to hold on to his wits. He was no different than the other pilots—movie star or not. All the pilots felt the cumulative impact of tough missions. Was his age a factor? It gave him wisdom for command, but operated against him after six or eight hours under constant and intense strain in the cramped confines of an airplane cockpit.

To be continued . . .

Recent Comments